A Q&A with Eisner-nominated comics creator and Sheridan College alum Michael Cherkas: Learning from Neal Adams, Harvey Kurtzman, Gerald Lazare and Ross Mendes; his long history of collaboration with creative partner Larry Hancock; and his new book, Red Harvest.

August, 2024

Michael Cherkas, one of Canada's top comic artists, spoke to GamutMagazine.org about his time at Sheridan College and working on Gamut, his long history of comics creation with creative partner Larry Hancock, and his new book, Red Harvest, which he calls "the most important graphic novel I’ve done.":

How did you get into comics/cartoons, and what ultimately brought you to Sheridan College?

Michael Cherkas: I grew up in Oshawa, Ontario, an industrial city about 30 miles east of Toronto, population about 70,000 in the mid-1960s. I started buying/collecting comics in 1965-66—primarily DC; the Weisinger-era Superman family comics, Batman, Detective, Flash, Sgt. Rock, Enemy Ace, etc. Then at the end of Grade 8 (1968), I started reading Marvel Comics. I had what might be called an “unhealthy” interest in comics. During high school I discovered EC Comics, The Spirit, the undergrounds (Zap, Skull, Bijou Funnies, Death Rattle, Freak Brothers, etc.) and European comics. There was a newsstand/pool hall/smoke shop in downtown Oshawa that sold Pilote and Tintin. It was in those magazines I first saw the comics by Jean Giraud and Hugo Pratt. I think Pratt was doing "Scorpions of the Desert" at the time. My high school French was terrible. But, those European comics were light-years ahead of what was happening in North American comics. I started to see the vast potential of comic books as a storytelling form.

By the time I was in Grade 11 or 12, I knew I wanted to be a comic book artist but didn’t see a path forward. I figured, I’d have had to move to the States and go to school in New York. Too frightening for a young lad from Oshawa. Then I saw an ad in a fanzine (RBCC—Rockets Blast and Comics Collector) for a comic book arts/cartooning program at Sheridan College in Oakville, Ontario. I think the Joe Kubert School in New Jersey had also just started operations around the same time. You may have to fact-check that.

And Oakville was just on the other side of Toronto! So I looked into it, and in Grade 13 applied to Sheridan College, much to the disappointment of my guidance counsellor. To make her happy, I also sent applications to three universities (Universities of Toronto, Western Ontario and Waterloo).

Sheridan is/was a community college. Tuition in those days was cheap like borshch. 250 dollars a year! It no longer is so affordable.

I went, showed my “portfolio” of high school art projects to Walter Hanson, the Course Co-ordinator and was accepted for the 1973–74 school year. In September 1973, I headed to Oakville with a lot of foolish dreams and much trepidation.

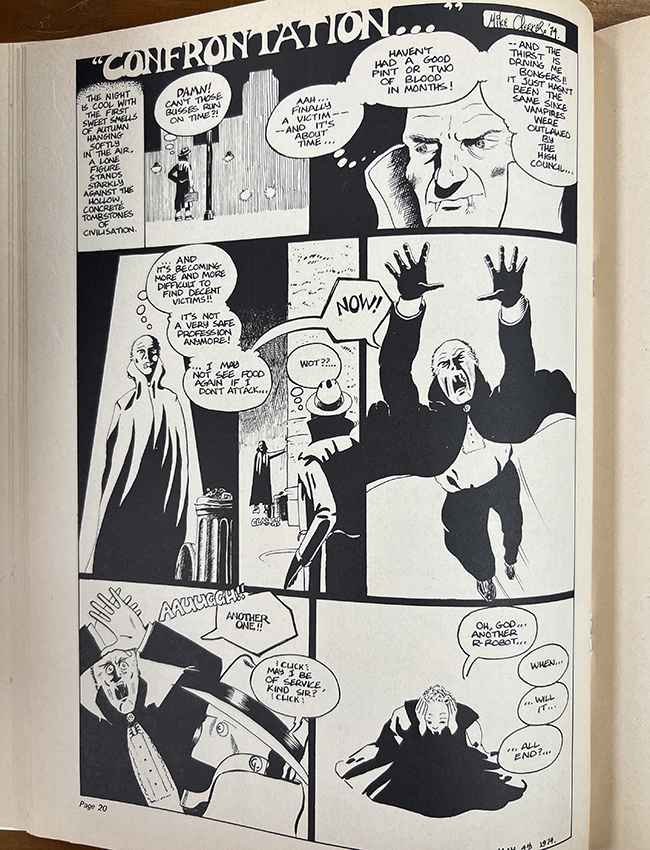

Which years were you at Sheridan and what was your involvement with Gamut? I know you had the piece “Confrontation” in the first issue, and Walter Hanson thanks you in the intro to the second issue, saying “Special thanks … to Mike Cherkas, letterer extraordinary.” I’d love to hear more about “Confrontation” and your other Gamut contributions.

MC: I attended Sheridan in 1973–74 and 1974–75. It was a two-year program. Though Walter Hanson offered a third year (a “graduate studies” year). I knew one student—John Ellis Sech—who took him up on it and I have a vague recollection of being offered the opportunity to do the third year. I declined.

Gamut was intended to be a showcase magazine for the program’s students. I contributed a one-pager to the first issue. There was some really nice work from another first-year student, Dave Matthews. His story—a western—was really nicely drawn. He could really draw. I think we all wondered what he was doing in the program. I don’t know what happened to him, if he ended up doing any comic book work.

"Confrontation" by Michael Cherkas, from issue one of "Gamut." Photo from my personal copy

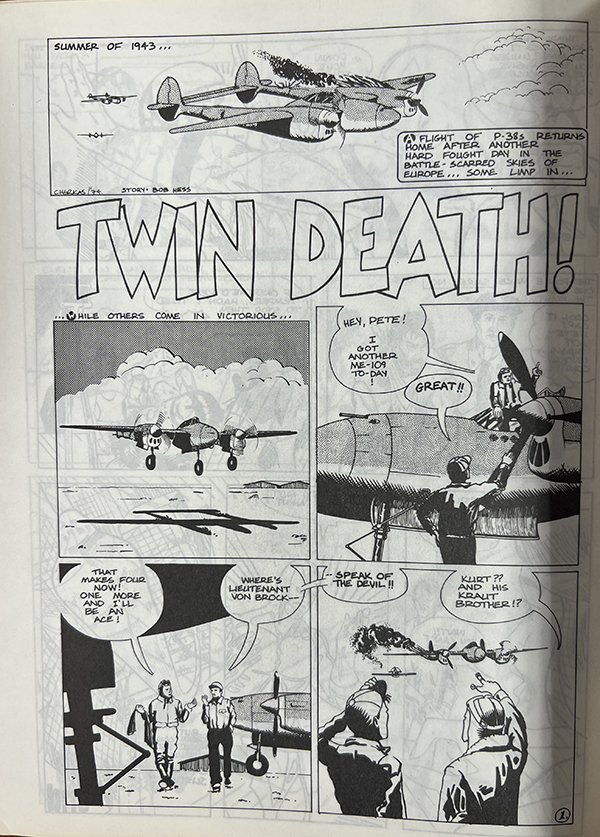

For the second issue (my second-year at Sheridan), Walter Hanson had me letter a few of the stories. For some unknown reason, he liked my lettering. And I drew “Twin Death,” a six-page EC-type World War 2 story, written by a first-year student named Bob Hess. I think we both had similar interests in comics. I loved airplanes. Still do. It gave me a chance to draw aircraft. Bob Hess was an American student. I have a vague recollection that he may have been from a military family. He may not have returned for the second semester. After leaving Sheridan, I lost contact with many of my classmates.

Looking at my Gamut stories I see both were done during 1974. “Confrontation” is dated “May 4th, 1974,” and “Twin Death” is dated “74” as well. It may have been my first-semester project in second year. What did I do during the second-semester? Could it really be nothing?

"Twin Death" by Michael Cherkas, from issue two of "Gamut." Photo from my personal copy

Do you recall what the press run would have been for any of the issues of Gamut? Approximately how many of each were printed/distributed? Also, there is an “error” version of the first issue, where the cover was accidentally printed without the red ink, and some made it out into the wild. Do you know any information about that?

MC: This is one question I have no answers to. I can only speculate about the print-run. A couple of thousand or so? Sorry. I’m of no help here. and I don’t know a thing about the mistaken print-run without magenta plate. Could be a “make-ready” sheet that inadvertently got bound in with the finished copies? I’m just speculating because after 40 years of working in the design business I’ve seen this sort of mistake, or worse, happen more than once.

It’s known that many famous working artists at that time, including Will Eisner, Neal Adams, Bernie Wrightson and Mike Ploog, were lecturers at the college. Are there other notable professionals who lectured there or with whom you interacted at the time that Gamut was in production?

MC: Here’s what I remember:

Will Eisner was there for a week or two during the first year of the program (the year before I attended). It was during that time that he began the five-page Tabloid Spirit story. The copies I have are copyright 1973. I had a bunch of these Tabloid Spirits. Walter Hanson gave me about 10 when I left Sheridan. I still have two copies.

During my time there, Eisner, Neal Adams and Mike Ploog came up to Oakville for one- or two-day sessions. Wrightson was there for a week or two. He spent much of his “lecture-time” drawing one page for a story he was working on. The only interesting thing I recall is that he started at the lower right-hand corner of the page, the exact opposite of most artists.

Adams was quite forceful during his lecture. I remember him telling us if we wanted to draw comics you better be drawing “16 hours a day. There were 24-hours in a day—seven for sleeping and one for eating and the rest for drawing.”

Adams also tore a strip off of one of the students in our class who complained about Don Heck, and wondered how he (Heck) continued to get work. Adams replied that Don Heck could “out draw anyone in the class. He was a consummate draughtsman, understood anatomy, clothing folds, drapery, perspective…” A few of the students were what we would now call “fanboys.” They didn’t really appreciate the unsung artists of the time like Pat Boyette, Don Heck and Jesse Marsh.

Vaughn Bodé and Harvey Kurtzman also were guest lecturers for short one- or two-day sessions.

Kurtzman may have given an overnight assignment. I remember Walter Hanson saying that when he comes around to look at your work, and if he says it’s “interesting” that means he really doesn’t like it. I worshipped Kurtzman. So the next day, he’s walking around the class looking at our work and he gets to me and says, “Hmm… that’s interesting.” And then he quickly shuffled over to the next student. I was shattered. But I still consider him one of my “comics gods.”

I think only Kurtzman and Eisner had the teaching chops. They both taught courses at the School of Visual Arts in New York. Adams was also good a trying to light a fire under our butts.

Our regular instructors were Toronto-based editorial or gag cartoonists. There was a local comic book artist, Don Marshall, who, during my first year, taught comic book illustration in the program. But I don’t remember if he taught during my second year there. And if he did, maybe he only taught the first-year students? He was quite a good artist. His style was reminiscent of Jeff Jones. I think he had stories printed in Orb and Andromeda, another Canadian science-fiction comic book published in the late 1970s.

During my second year at Sheridan, I spent more time in Toronto (I lived at a student residence in downtown Toronto during second year) than at Sheridan. I think I went to class only two or three days a week.

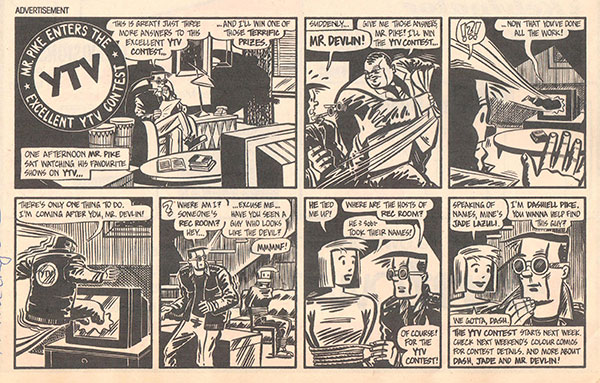

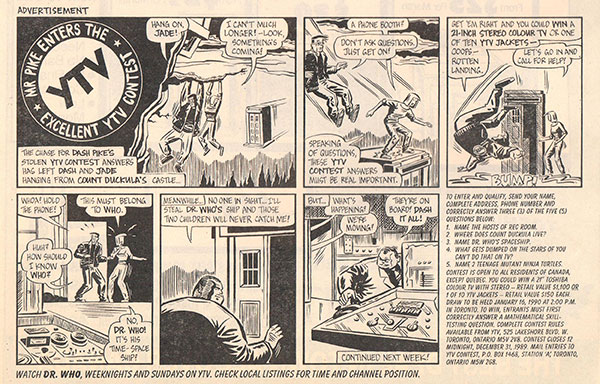

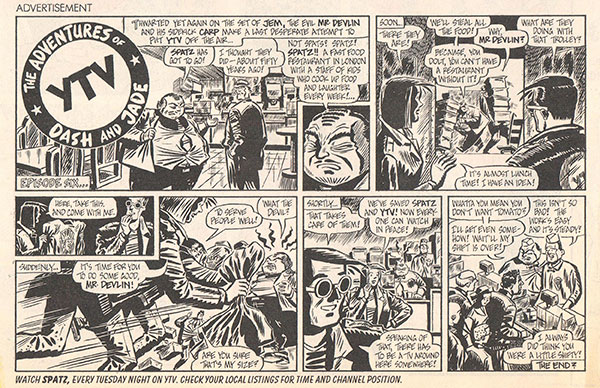

From Michael Cherkas: "These three are random episodes from 'The Adventures of Dash and Jade,'' the advertising strip I drew for YTV, a cable network in Canada. I think this would have been in 1989 or so. Programming on this channel is directed towards kids and young teenagers.

These were scanned from printed newspaper copies. Once the art was turned into the ad agency, it disappeared.

The only vaguely interesting thing I remember about this is that the writer—an advertising copywriter—had no idea about how to write comics.

Oh, and the villain, Mr Devlin, is patterned after my Sheridan pal John Ellis Sech."

Click on each image to view a larger version

We had one instructor, Ted Martin, who though a gag and strip cartoonist (he wrote and drew the syndicated strip Pavlov), was quite good at teaching. He started teaching in the second semester of my first year at Sheridan (January 1974). He put a lot of emphasis on life drawing. During second-year, he also drove me back to Toronto every Wednesday after class. He was also quite supportive of those of us who wanted to follow the ridiculous dream of being a comic book artist.

By the time I graduated from Sheridan, I knew that I didn’t really want to be main stream comic book artist. I couldn’t draw super-heroes to save my life, didn’t want to draw them and at that time, that was pretty much what you’d be drawing at Marvel or DC. And if you wanted to break-in to comics you had to move to the New York area. Very few from Sheridan took that route. Jim Craig did. He could really draw super-heroes. I think Jim taught at Sheridan after he returned from New York. But that would have been after I graduated.

I shouldn’t be too critical of the program. They were the first college to offer something like this. And were probably making it up as they went along.

The most important thing I learned at Sheridan is that drawing comic books is really hard work.

Can you recall one or two fond memories or anecdotes from your time at Sheridan?

MC: No anecdotes to speak of. Except for the time we all had too much beer at the Riverside—an old, down and dirty Canadian bar (6-oz. drafts, tiny arborite tables, pickled eggs and sausages) at a year-end party in May 1974.

The cartooning program felt sort of fake. The instructors weren’t very good—except for Ted Martin. The other two editorial/gag cartoonists who were instructors actively disliked comic books. Most days the students sat on the bleacher seats that surrounded our studio space talking about: the previous night’s guests on Johnny Carson (The Tonight Show); any movie recently seen; the latest rumours in the comic book industry (usually bleak); or wondering why Clint Eastwood doesn’t play Batman in a movie. We would often go to Toronto to hang out, especially if there was nothing pressing to do at school. Usually there wasn’t.

One night John Ellis Sech and I went to Toronto to see a WHA hockey game at Maple Leaf Gardens. He was from southern Ohio close to West Virginia. He was born in West Virginia and his family moved to southern Ohio after his father suffered a mining injury. John had never seen a hockey game. So I said what the heck, we were in Toronto for the day. I suggested we go. The Toronto Toros were playing a team from Ohio—either the Cincinnati Stingers or Cleveland Crusaders. We bought cheap nose bleed seats up in “the greys.” The arena was half empty, maybe five or six thousand “fans” were in attendance. I suggested to John that we move down to the greens or even the blues. But John was honest. He said in his West Virginia accent, “Mike, we paid for these seats, so we gotta sit in them.”

He moved back to Ohio after 1976 or 77. He came up to visit in 1979 and 1980. I know this because he helped me move into an apartment in 1979 and was at my wedding in 1980. I stayed in touch with him until he died in 2009.

You, along with several other Sheridan talent, were involved with Orb at around this time as well. How did that come about, and what memories can you share about working on Orb? I know Orb founder and Editor-in-Chief James Waley was at Sheridan around that time as well, correct? Were you students when Orb was first being created?

MC: Orb was started by James Waley and Matt Rust. They were second-year students during my first year at Sheridan.

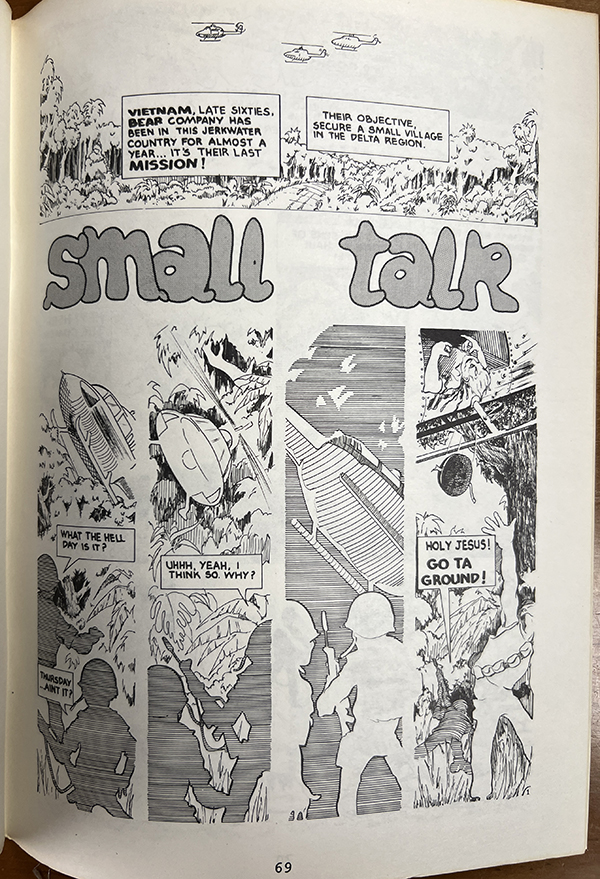

My involvement with Orb was only as a sometime letterer. I don’t have much information or tales about working on the magazine. Although, in the second issue, a four-pager titled “Small Talk” was printed. It was written, pencilled and inked by four or five students from the Sheridan cartooning/comic book arts program.

James Waley and Matt Rust were planning a companion humour magazine called Tilt. I was assigned a story for that but the magazine was cancelled before the first issue was published.

"Small Talk," from "Orb" issue two, done by Sheridan Cartooning Program students. Photo from my personal copy

You worked on books like Cerebus, Cheval Noir and more, and found success at Renegade Press with The Silent Invasion. Your collaboration with Larry Hancock also led to other projects like Suburban Nightmares and The Purple Ray. First: Do you have any anecdotes of working on Cerebus? And second: How did the partnership with Larry Hancock come together, and what’s it been like to see The Silent Invasion have such long-standing success, from being nominated for a Kirby Award in 1987 to NBM’s volume 4 published just a couple of years ago?

MC: This will be a long answer. When I left Sheridan in 1975, I applied to the Ontario College of Art (OCA) in Toronto. As I indicated earlier, the Sheridan program wasn’t very good at teaching art skills, so I figured I better try to get more training. I needed to learn to draw.

At OCA, I was in the Communication and Design Program which taught advertising, typography, corporate and publication design, and illustration. I spent most of the four years there taking illustration, life drawing and publication design courses. I spent too much of my youth reading Mad Magazine to take advertising seriously. The closest I got to advertising were the “marker-rendering” courses.

One of my illustration instructors, Huntley Brown, taught me more about comic book illustration in one half-hour session than any of the instructors at Sheridan. Huntley Brown was a successful editorial illustrator. During the 1950s and 1960s, he contributed to the weekend magazines (Star Weekly, Weekend Magazine and The Canadian Weekly) that came with the Saturday newspapers, as well as Canadian magazines like Maclean’s, Chatelaine and Saturday Night. It turned out he always wanted to be a comic strip artist. He grew up when Terry and the Pirates, Flash Gordon and Prince Valiant were the mainstays of the Sunday comics sections. He loved Milton Caniff, Alex Raymond, Will Eisner and Hal Foster. I think he was thrilled when I told him I’d like to do a short comic book story as my independent project during fourth year.

I did a short story with John Sech called Dick Mallet for one of Huntley Brown’s classes as an independent full semester project. He tore the layouts apart. Talked to me about camera angles, perspective, pacing, drawing the reader in with dramatic panel layouts. He understood the form. I went back to my room and redrew the whole thing.

One last thing about OCA. Two of my instructors, Gerald Lazare and Ross Mendes were, in their previous lives, comic book artists who worked on the “Canadian Whites,” the wartime comic books produced in Canada during World War 2. They were nicknamed “Canadian Whites” because the books were printed in black and white. Canadian kids didn’t need colour in their comic books.

During the late 1970s I contributed three short Dick Mallet stories to the Canadian Comics Annual and a sister publication called the Canadian Children’s Annual. All were scripted by John Sech, with editing by Larry Hancock. John couldn’t be credited on these stories because he was American.

Larry, John Sech and I also did a Dick Mallet story for the 1981 Captain Canuck Summer Special. That particular Captain Canuck Summer Special never saw print. But we did print the story in one of Caliber Comics Silent Invasion reprints in 1996.

In the early 1980s I sent Dick Mallet samples to Deni Loubert at Aardvark-Vanaheim for their Unique Stories back-up feature in Cerebus. She got back to me and agreed to a two-part Dick Mallet tale and then a few issues later, a three-parter. Larry Hancock worked on these with me.

And this is where I need to backtrack as Larry has entered the scene…

I met Larry when I was in Grade 10 in Oshawa. He was in Grade 11. He lived in Whitby, Ontario, then a small town (population 8,000) immediately to the west of Oshawa. It’s no longer a small town (current population 140,000 and growing).

We met at Morgan Self’s, an antiquarian bookseller in downtown Oshawa. Morgan Self carried a large selection of recent back issue comics. In the imagination of my memory, I hung out there every Friday night searching for old comics. They were priced at a nickel or dime or a quarter, or egads!, even fifty cents! We would spend hours in the store searching through the bins of “old” comics for that missing Spider-Man or Lois Lane or Deadman, and then until closing time, we’d regale Morgan Self with our fanboy opinions on the current state of comics.

Morgan Self was quite patient with us, allowing us to ramble on about Batman, Alex Toth, Marvel or DC, Jack Kirby, why doesn’t Neal Adams draw more stories?, Asterix and Obelix, Uncle Scrooge, Carl Barks, the old Sunday strips, Plastic Man, EC Comics, Steve Ditko, O.G. Whiz, Will Eisner, etc. I’m surprised he didn’t kick us out and ban us from the store.

While in high school, Larry I collaborated on early fannish attempts at creating comics. I think I may have shown one of these sorry attempts at comics to Walter Hanson during my portfolio review for the Sheridan program.

When he went to university in Waterloo, Ontario and I was at Sheridan, and then OCA, we continued to correspond. talk about comics and collaborate on more fannish comic book stories.

We both still live in Toronto so collaborating continues to be fairly easy.

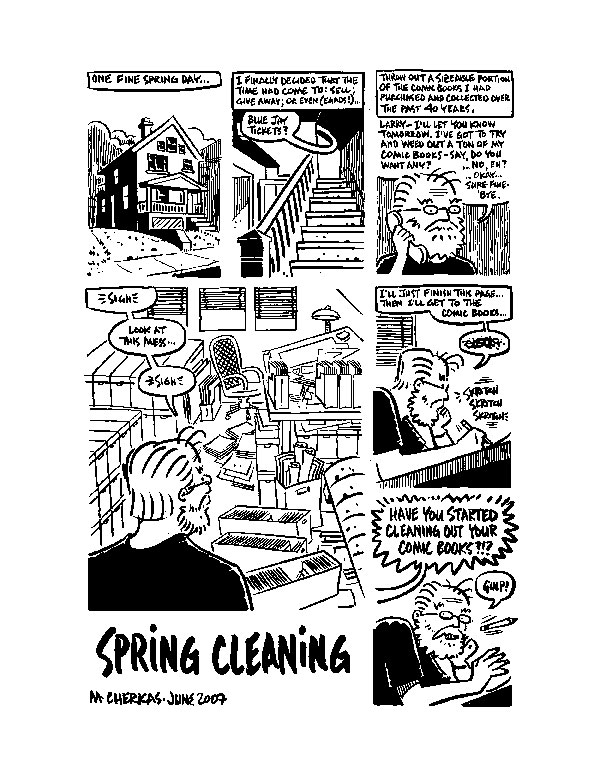

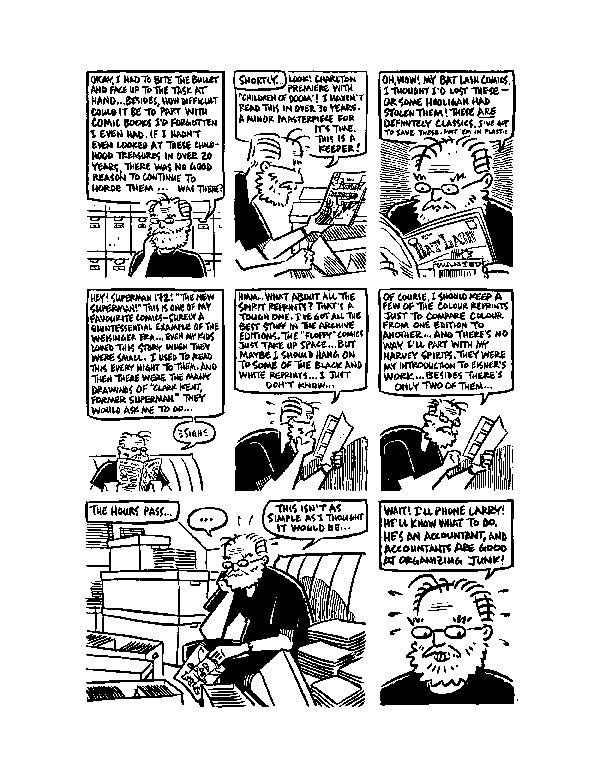

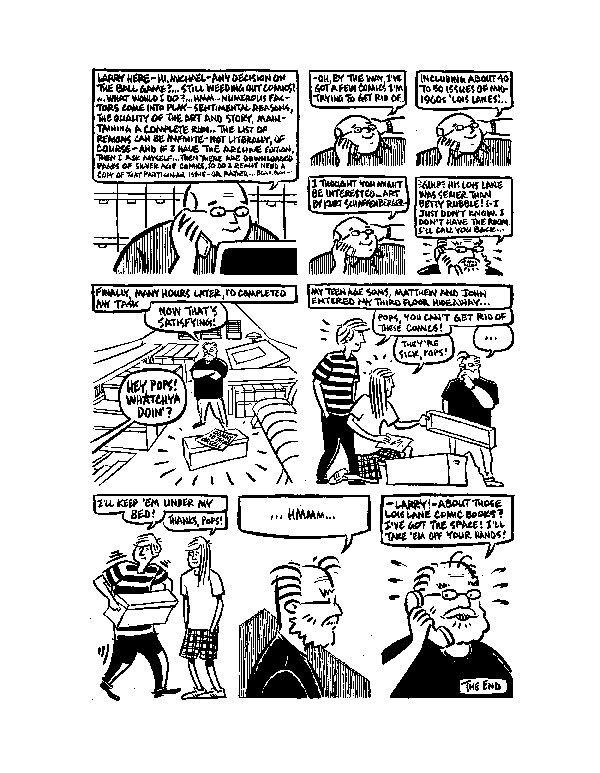

From Michael Cherkas: "Here is 'Spring Cleaning,' a three-page story I did for the Comic Eye, an anthology edited by Mark Innes, published by Blind Bat Press. According to Amazon it was published in 2007."

Click on each image to view a larger version

Now back to my post-OCA years…

When Deni and Dave Sim split, she started Renegade Press. She was looking to expand the line and asked Larry and I to develop a book for them. This would have been sometime in 1984 or 1985.

We initially wanted to propose Dick Mallet as a regular 24-page bimonthly. Deni said no as she was already publishing a detective series Ms Tree by Max Allan Collins and Terry Beatty.

We developed The Silent Invasion, combining elements of paranoid noir-ish detective fiction with B-movie sci-fi of the 1950s. We prepared a long, detailed proposal for her (that still included Dick Mallet as a minor character); then drove to Kitchener, Ontario—where she was still living before moving to Long Beach, California—and gave her our presentation. She may have accepted it at that meeting.

Once we got the go-ahead for The Silent Invasion, my biggest concern was that I would have to quit my job as a graphic designer at a Toronto design studio. It was fairly well-paying, but I was getting frequent stomach aches from the relentless deadline pressure. And my wife and I had just bought a house in Toronto and had mortgage payments. My wife said, “You can quit your job but if the comic book doesn’t work out…”

So I quit the design studio in October or November of 1985, and began to pursue a wild and crazy dream.

The first five or six issues of The Silent Invasion were fairly successful, but the black and white indie market collapsed during 1987. Sales dropped. Even so after we finished the 12 issues of The Silent Invasion, we thought we’d continue with Suburban Nightmares. Suburban Nightmares was a collection of short stories. I didn’t have as much time to spend on it as I was doing more freelance work. So we contacted John van Bruggen to help with the art chores on the book. John was a friend/colleague from our comic book collecting days in Oshawa.

After we finished Suburban Nightmares, I co-plotted and drew a five-part story for Heavy Metal called The New Frontier — not to be confused with Darwyn Cooke’s absolutely stunning and amazing DC’s The New Frontier. My New Frontier was an alternate-universe story written by John Sabljic. Dark Horse serialized it as three-issue mini series, and then NBM collected it in 1996.

By the early-1990s I was back working in the graphic design world.

But Larry and I continued to dabble in the world of comics. That’s what we are — “dabblers.” I don’t think I mentioned this, but Larry is a Chartered Accountant, or as they are called now a CPA.

We wrote and drew a couple of Suburban Nightmares stories for Cheval Noir and Negative Burn. Then in the late 1990s, we did another Silent Invasion mini-series titled “Abductions.” NBM serialized it as a five-issue floppy comic, but didn’t collect it until 2020 as part of The Silent Invasion reissue. Because of COVID restrictions we never had the chance to promote it properly. It landed with a resounding “thud.”

In 2012, Larry and I published our “ash-can” edition of the The Purple Ray. It’s a somewhat satirical take on the super-hero business, and an outsider’s look at the comic book business. It’s a project that’s been sitting around for 12 years.

We completed the fourth Silent Invasion, “Dark Matter” between 2016 and 2020. And most recently contributed a five-page story, “Talking to a Hill” to Comics for Ukraine, a fund-raising anthology for humanitarian aid to Ukraine. The collection won the Eisner Award for Best Anthology this past July. “Talking to a Hill” was nominated in the short story category.

With Red Harvest now finished, we’ll have time to complete The Purple Ray. It’s planned as a 120- to 144-page graphic novel. If all goes well, we should complete it in two or three years.

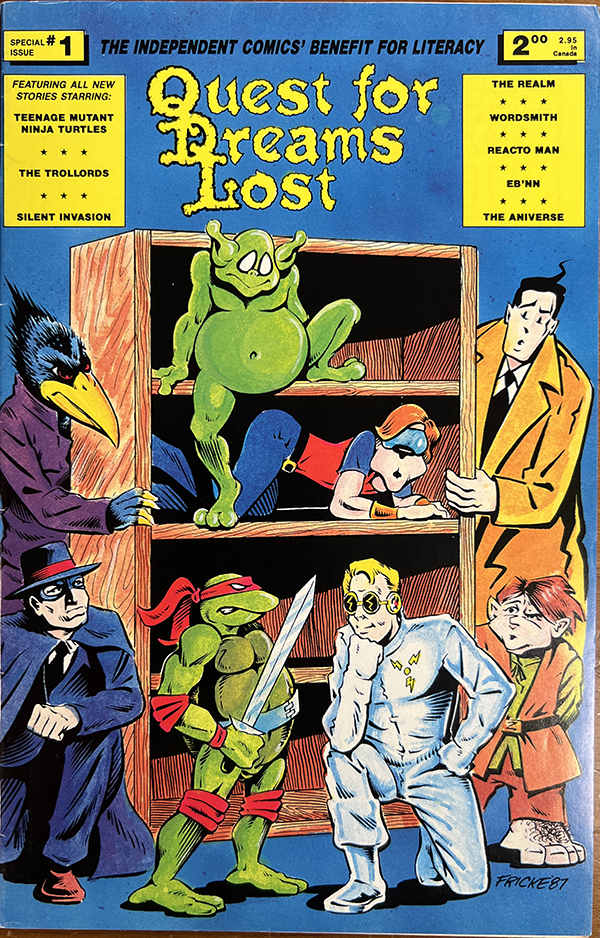

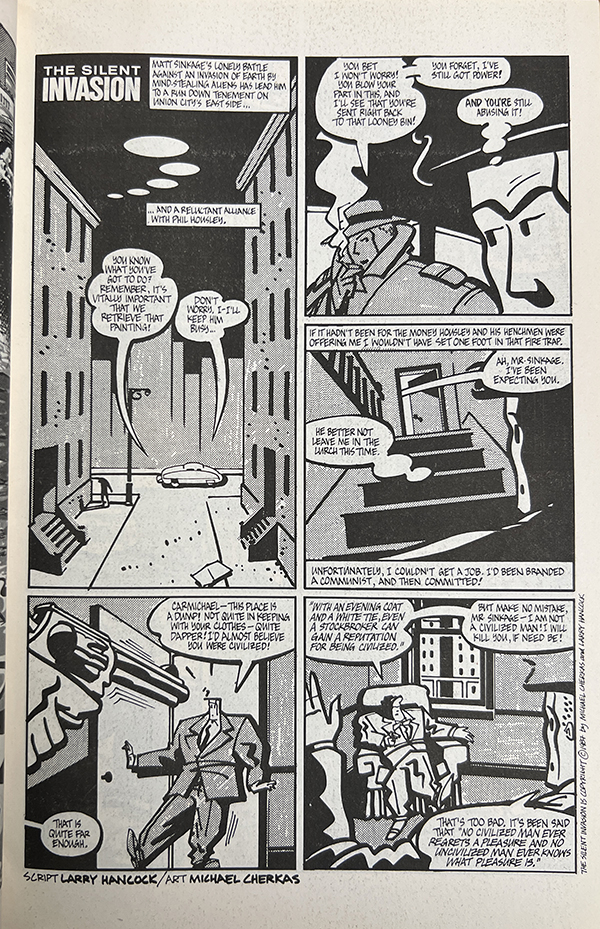

This is kind of a strange aside, but The Silent Invasion was included in Quest For Dreams Lost, which was a fundraiser comic for the Literacy Volunteers of Chicago. Do you recall how that came to be?

MC: I think we must have been asked to contribute to this project at the 1986 Chicago Comic Con. In 1988, we contributed a two-page Suburban Nightmares story to the first issue of True North, a benefit comic for the Comic Legends Legal Defence Fund here in Canada.

Cover and interior page of "Quest for Dreams Lost," featuring "The Silent Invasion" by Michael Cherkas and Larry Hancock. Photos from my personal copy

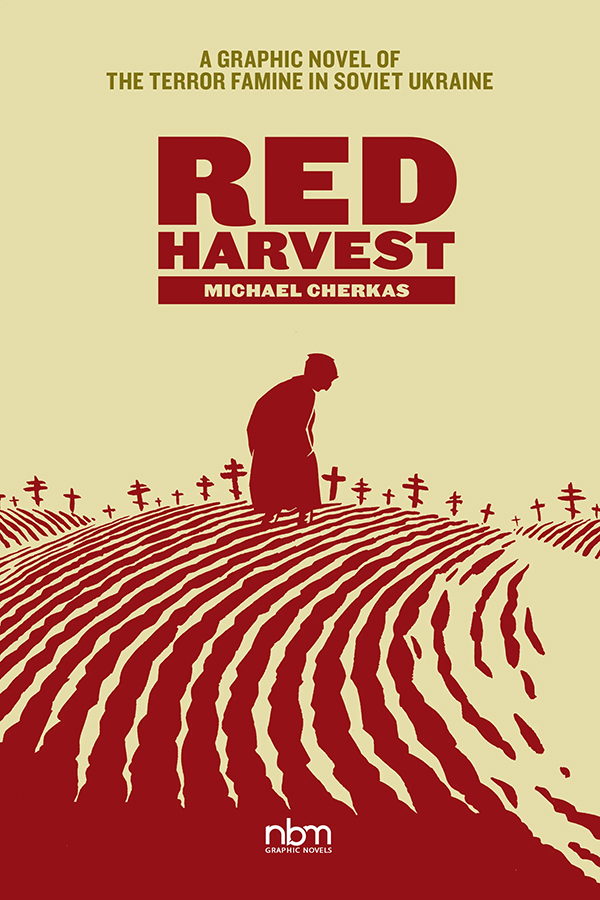

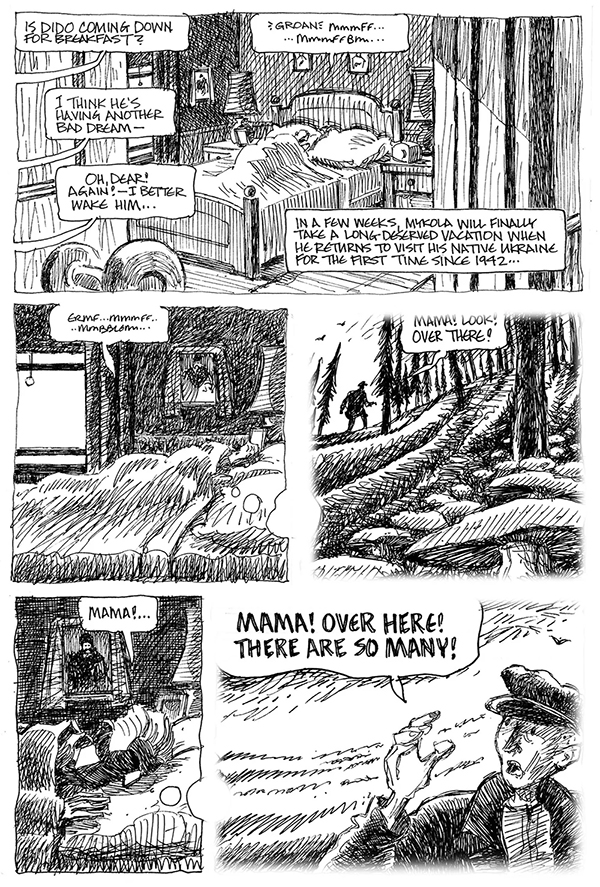

Your latest book, Red Harvest, is a fictional story of the famine in Soviet Ukraine in the early 1930s, based on survivors’ anecdotes. As a Ukrainian-Canadian author and artist, how important was it for you to tell this story – was there an added sense of responsibility you felt as you were writing and drawing the book? How does that emotion and historical significance play into how you translate the survivors’ experiences to the drawn and written page?

MC: As a Ukrainian-Canadian telling this story was important. Definitely the most important graphic novel I’ve done.

But it’s a story I never really thought I would draw. If you would have asked me in 1990 or 1999 if I wanted to draw a story about the Holodomor, I would have said “yes, but no thank you.” It is a very difficult topic. At the same time I wondered why other cartoonists had never told this story. Since then, others comics about the Holodomor have appeared (Russian and Ukrainian Notebooks by the Italian cartoonist Igort and Five Stalks of Grain by Ukrainian-Canadians Lysenko and Galadza).

When I began this project with James Waley in 2009, I was quite hesitant about doing it. I didn’t have the “artistic chops” to draw such an emotional and very dark story. But after diving deeper into the research, I said to myself, “I can do this thing. I can take it on.” I knew quite a bit about the famine. I was aware of it since I was a kid.

My father would often talk about the famine, even though he was from western Ukraine and came to Canada in 1928. He didn’t experience it. But he knew famine survivors living in Oshawa who had come to Canada after World War 2. Ukrainian and Soviet history is/was one of my interests. I’ve been reading biographies of Stalin since I was at Sheridan College. He is my “bête noir.”

Getting back to your question, though. Once I really got going on the project, I did feel a sense of responsibility; that it was important to tell this story. It’s a hidden genocide due to Soviet propaganda campaigns against Ukrainians, and the willingness of “the west” to turn a blind eye to this tragedy while it was happening, and afterwards ignore it until the late 1980s. To this day, Russia, as the “successor state” to the Soviet Union, refuses to acknowledge it. They claim it was a Soviet-wide famine.

There were excess deaths by starvation in grain producing regions of Russia in 1931 and early 1932. But, in many of these areas of Russia, like the Kuban, the population was majority ethnic Ukrainian. Kazakhstan also suffered terribly during these years. Two million out of a population of four million died from starvation as the misguided and brutal Soviet authorities tried to force a traditionally nomadic people onto collective farms and turn that area into a grain-producing region.

In 1932, Ukraine, specifically was targeted with the introduction of the “five stalks of grain” decree in August 1932; with the draconian “blacklisting” of Ukrainian villages; in November 1932; and, the introduction of the internal passport which blocked Ukrainians from travelling to other parts of the Soviet Union in search of food.

It’s important that more people are aware of the Holodomor. If you are aware of what has gone on before in 1932 and earlier in Ukraine, then the current Russian invasion isn’t all that surprising. If Red Harvest helps in informing others about this previous tragedy, then the book has been successful.

###

Michael Cherkas' latest book, Red Harvest, as well as collected editions of The Silent Invasion, are available at NBM Graphic Novels. Click on the images below to buy a copy of Red Harvest today: